First Step: Premise ✧ Next Step: Concept

So far this month I’ve discussed fiction genres and narration with an eye toward helping those planning on writing during National Novel Writing Month. It can be handy to start big and work inward, so the tasks so far have only been general. This week we start getting serious. This is a big entry, so take it in stages! I’ve given suggestions for starting to brainstorm on characters, setting, and plot, but I’ll be getting into them in more detail in coming weeks, so if you don’t have everything you may need yet, that’s okay. We’ll get there.

If you still don’t have an idea for NaNoWriMo yet, consider using a random idea generator like the ones on the Seventh Sanctum site. Most of these generators are formulaic, but that doesn’t mean throwing random elements together won’t spark a good story! If you have your big list of things you love in stories from the first week, try combining some of them in odd ways to see if you can make something interesting. Perhaps merge a few items from that list with the random generators, create something altogether new.

Turn Your Ideas Into A Premise and Concept

Now we come to the heart of NaNoPrepMo, the ever elusive concept. Ideas are all well and good, and most writers find they have far too many to know what to do with. (Like a certain blogger with no clue what she’ll be writing for NaNoWriMo… still.)

The goal this week is to start distilling ideas you have into a more focused concept. Any and all brainstorming you’ve got is good, and it will help you with this. The first step is to figure out a premise that you like.

Keywords: Premise vs. Synopsis vs. Concept

Note that a story premise is not the same thing as the full story synopsis you’d send to an agent or publisher, which details all the major plot points of a story from beginning to end, character motivations, and contains pretty much everything your story will entail, up to and including the ending. Our goal here is a premise, just a focused couple sentences that include the meat of the plot, namely the primary character(s), inciting incident, and the primary antagonist or opposition. First get the premise written down so you can refer back to it, and then expand it into enough detail you can write your story. The expanded concept starts with the premise and then builds in much of the same information you would provide in a synopsis, but is written as a break-down for you, rather than an engaging explanation of how the story goes.

Let’s start with the simpler of my favorite two ways to condense your story into a short premise blurb.

Story Skeleton

A long time ago I found Jim Butcher’s blog, where early on he was posting writing advice for other writers who want to turn their ideas into reality. (I think he has since moved to posting updates on his website, though I’m not certain if writing advice is part of it.) The post where he described what a story skeleton is was apparently from 2004, so it’s certainly been longer than I realized! I’d encourage everyone to read the full article, because he has a lot of good points. This is a very simple description of your story, but being simple does not make it easy. The story skeleton (or story question) is broken down into the most basic pieces of information, like so:

*WHEN SOMETHING HAPPENS*, *YOUR PROTAGONIST* *PURSUES A GOAL*. But will they succeed when *ANTAGONIST PROVIDES OPPOSITION*?

Simple enough, right? Yet it’s harder than it looks. See if you can fit your ideas into this skeleton, and then stare at it for a little while. Did you cover everything that is at the heart of your novel? Does the inciting incident include why it’s of import to the character? If not, rewrite that phrase/clause until it’s obviously a critical moment. Here’s Jim Butcher’s own example: “When a series of grisly supernatural murders tears through Chicago, wizard Harry Dresden sets out to find the killer. But will he succeed when he finds himself pitted against a dark wizard, a Warden of the White Council, a vicious gang war, and the Chicago Police Department?”

It’s somewhat of a given that ‘grisly supernatural murders’ are critical. Murder usually is. But look at the details that are also included in that first clause. A series of murders adds to the concern, and tearing through Chicago establishes where the story is set as well as some of the conflict right there. Supernatural murders in Chicago? Probably not something the cops are prepared for. Whatever your catalyst, it needs to be clearly motivating enough to make your character(s) change their routines and go after it.

This is really the key to your plot. There may be side plots, or diversions thrown in as plot twists, but all of it really boils down to the main character(s), some event that pushes them to act, and the obstacles in their way.

Craft Your Flexible Outline’s Premise

The seven-step process I like most for putting ideas to paper before writing, which the creator K.M. Weiland dubbed the Flexible Outline, can be found here. She has written a number of books on the subject, but that linked article alone has changed how I go about my pre-writing process.

She, too, wants to see a couple sentences outlining the premise of your story. Here’s the example she gave: “Restless farm boy (situation) Luke Skywalker (protagonist) wants nothing more than to leave home and become a starfighter pilot, so he can live up to his mysterious father (objective). But when his aunt and uncle are murdered (disaster) after purchasing renegade droids, Luke must free the droids’ beautiful owner and discover a way to stop (conflict) the evil Empire (opponent) and its apocalyptic Death Star.”

You can see how the starting situation is going to have to change, whether the protagonist gets his desire/objective or is simply rushed along by the plot from the disaster onward. You also have a sense of scope, with things going from a very narrow worldview to renegade droids, an evil Empire, and of course, the Death Star. I think the only step up here from the story skeleton is that the starting situation is included specifically, rather than just implied, and that will be your starting point when you begin plotting.

Have you come up with a premise you’re happy with?

Have you come up with a premise you are satisfied with? If not, STOP HERE. Nothing after this point will be of use to you until you have that premise crafted. Your task is to spend some time brainstorming characters, settings, and plot points until you have a better idea of the story you’re writing. Follow multiple tangents. Ask “what if?” of every plot point, setting, and character trait. Second-guess your choices to see if there are better fits. Could your main character be a different gender? Could you set your story two hundred years earlier? Could your antagonist actually be your hero and spin everything relative?

Expanding Your Premise Into A Concept

Before you can really claim to have an entire concept for your story, you’re going to have to work on three things: characters, setting, and plot. Depending on the order you want to go about it, you may already know some of these, or you may still be working on them. If you have a great setting and a timeline of events, you need characters to bring it to life. A character without context doesn’t do you any good, either. Whether you do this on pages in a notebook or on index cards so you can move them around and see the story start to take shape doesn’t matter. What does matter is that you have some characters, some setting details (organizing settings can be very individual to any story, so whether you describe the world top-down or set individual scenes and then connect them is up to you), and some scene ideas loosely organized. The NaNo Prep 101 exercises may help you a good deal here, and I find their “Jot, Bin, Pants” plotting method is a good way to start if you’re still uncertain. In short, you write things down on index cards, drop them in beginning/middle/end bins and go from there. I’d add a characters bin and a setting bin if you like that, or do whatever works best for you! There’s no single right way to go about writing a novel.

This is the beginning of your Story Bible! If you missed it, check out this article by J.M. Butler on creating your Story Bible. Whether you do it in a three-ring binder, notebook, or software of some kind, your Story Bible is the reference material you’re going to be going back to all throughout November as you write. You don’t need to have a plan for your Story Bible yet, but this is where you start. Index cards dropped in piles are fine! Rough groupings of cards can be organized as you go into clearly organized sections later.

Characters

I am a believer in the power of characters driving the story, so I always suggest starting with your main character(s). Each character needs to be compelling, a real person given a chance at something interesting (inciting incident), with some desire above all others, and a situation that is keeping them from realizing that desire. In general we tend to have pretty classic ways to set up the character for big things. I recently tried to explain how much detail was needed to have a solid sense of the character as follows, basing the explanation on the first Harry Potter book:

Compelling Character: A boy orphaned by the death of his parents “in a car crash”.

Desperate Desire: He wants to belong, to be part of something.

Specific Situation: He was never enlightened about wizardry, and is currently living under the stairs at his awful relatives’ house, who oppose just about everything he does on principle.

Classic Setup: “The Boy Who Lived” (Chosen One trope)

There are a few more things I try to get laid out, because they guide the story and tell you what additional scenes you’ll need to organically grow your character into the hero they can be. All characters have some kind of hurt they’re nursing, something that makes them not always choose wisely, and they have a flaw. Flawless characters are boring. Their flaw tends to be why they falter in their goal, and it is tied to their wound. Consider Severus Snape:

Wound: Lily picked James instead of him.

Flaw: Pushes people away.

I chose not to use Harry Potter for the purposes of this example because in the first book, as with many coming-of-age stories, his issues are often related to inexperience and lack of required knowledge. The purpose of the story is to grow as a character. For that to work, all plots have to start with something happening that changes the character(s) as we’ve established them in the opening chapter(s). Whatever it is, it’s completely unexpected, and changes the course of the character (and thus the book) for good.

Inciting Incident: Magical envelopes start showing up. “You’re a wizard, Harry.”

Quirk of Fate: Not just any wizard, either, everybody knows his name. He’s famous.

Theme: Love conquers all.

With those nine points, you can provide the basic information for any character in any storyline, and have enough information to work on the setting and plot line. Sometimes you may start working on scenes and realize there are holes, possibly because you need a second character to balance things out. Keep at it, with the character template above you can jot down new character ideas as you go. (These can fit on a notecard, should you be the hands-on type.)

Setting

Some stories don’t require much of a setting, rarely more than place names, maybe the cafe the characters meet at, their homes, and that’s it. If your story is set in the real world, you can read the top suggestions and then probably skip past most of my other advice entirely, unless the following applies to you; authors of fantasy, science fiction, thrillers, or westerns… you all have to read further, because your settings need more involvement. Thrillers can be set in the real world, but they need more careful planning because often the way the scenes are presented in a given setting is part of the purpose of that scene.

If you’re writing in the real world, your setting can be much narrower, such as a town or city, or several linked by various modes of transportation. For you, the only differences in setting are going to be the individual locations, real or fictional, such as the main character’s home, the restaurant or bar they meet their love interest at, and wherever else the events of the story take place. You may not even need to plan too hard at this stage, because you have reality as the big picture and that’s pretty well documented already. I recommend creating index cards or notebook pages for each major place, even if you don’t fill them out until later. That way you don’t have to keep returning to Google to search what the main street of town looks like. For a novel I’ve been working on recently, I made two groups, one for each of the two side-by-side towns in which the two main characters live, work, and interact. Town A had the hero’s apartment, his starting workplace, and a restaurant the hero and heroine went to on a date. Town B had the heroine’s workplace, and so on. This way I could always easily find details I was looking for.

For those not writing in reality, or those who need more details laid out early, at the most basic level, you need to write down the big-picture setting, whether that’s “England in the 1600s but with vampires” or “planet hopping across the Milky Way in search of a great sage who doesn’t want to be found”. Consider a few things, and really your baseline is reality right now, so your setting details only need to be to the extent that your setting is not like that baseline. England in the 1600s may be fairly well detailed, but how does the addition of vampires change it? Are they hidden powers behind the throne, or are they widely known? Planet hopping is going to be an even bigger unknown, because you have nothing at all to base it on. How do your characters travel? Are they spending time in space, or do they teleport straight to a new planet like in Stargate? How many planets do they visit? Each planet needs to be different, and there may need to be large sections mapped out or detailed in your notes for the plot to transpire.

What’s the mood you’re conveying? Is this a murder mystery, where most of the setting will feel dark and mysterious until there’s action and blood and screams? Are many scenes set in the light of day or are they shrouded in night? I like to think in terms of polarities, so light or dark, warm or cold, or the themes of seasons like springtime growth and life compared to winter’s hidden life and ice. Whatever works for you, try and get some themes in here while you’re at it.

Are the inhabitants of your setting human? If not, you may need to spend a while just developing your alien or fantasy species. For the purposes of your concept, jot down some notes and move on, you’ll have more time to deal with the worldbuilding later. Tip: It can be handy to write notes to yourself based on your favorite movies or pop culture references, because you immediately know what those mean without needing to write down every detail. As long as you do, eventually, expand out from there, it’s okay at this stage. (Maybe you’re writing fanfiction and that’s the sum total, I don’t know.)

Who’s in charge? You may or may not run into them over the course of the story, but there’s usually some kind of authority figure that plays a role, even if the authority applied to the story is really just the characters’ own morality. What’s the structure of the place, are there police and democratically elected officials? Or is this the sort of place where there’s a village elder who knows all (and if they don’t know it, you’re out of luck)?

What’s the technology level? Whether you’re in the Stone Age, the Digital Age, or Post-Singularity, your characters and the way they travel or communicate will be in part derived from the technology of that era. Because I’m a nerd, I actually think back to the first place I saw this quantified, which was the GURPS System rulebook, the section on Tech Levels. If you are writing a setting that isn’t 21st century reality, the charts on that wiki may do you a lot of good; they lay out what transportation or weapons look like in different eras, and what power or medicine is available. (No batteries in Ancient Rome, thank you very much.) Very handy if you’re trying to build settings based on magic, too, because you can check that chart for the minimum things people without magic would need to be able to do, and then how much easier magic makes life on top of it. And don’t forget Clarke’s third law: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” If you’re the handwave it sort, that law is your friend.

Now, go back and write out some of the settings specific to the characters lives, or to scenes you have in your head. Perhaps it’s time to talk about those scenes, and you can get back to writing the settings down as you go.

Plot

I often don’t have more than a vague beginning and ending when I start an idea. I know the inciting incident and I know roughly where I want the novel to end up. For me, the middle is one big gray area until I work at plotting out some scenes. Depending on your concept at this stage, you may already have most of the story in your head. Great! Write it down. If you’re the organized type, you probably don’t need me to tell you how to go about it! I can also link you to the range of options the NaNo Prep 101 workshop offers for plotting next week. I’ll be diving into more on plot methods next week, too.

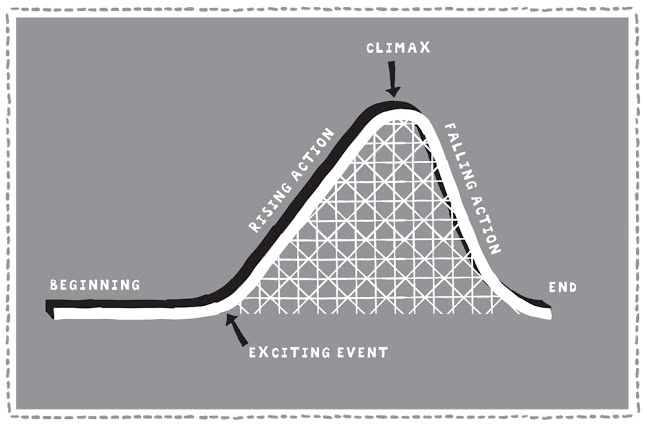

Outlining isn’t for everyone, and some of you just cringed reading the word. If that’s you, keep reading. I’ve learned that if I go into November without any plan at all, I get lost very quickly, especially when life hits you with a sucker punch. Given that it’s 2020… we may all want to plan some contingencies. Once upon a time someone I knew referred to this as “pantsing responsibly”. I love that phrase, and will shamelessly apply it everywhere I can. Regardless of your organizational preferences, I think we can all agree that the following structure is pretty universal:

Part 1, Setup: Introduce protagonist, hook the reader (including the inciting incident), and set up First Plot Point (foreshadowing, establishing stakes); major goal is establishing empathy (not necessarily likability) for the protagonist.

First Plot Point. The first real encounter with the enemy. This gives us new information, shows the hero what he’s up against, and gives the hero the reason to fight for his goal.

Part 2, Response: The protagonist’s reaction to the new goal/stakes/obstacles revealed by the First Plot Point; the protagonist doesn’t need to be heroic yet (retreats/regroups/doomed attempts/reminders of antagonistic forces at work).

Midpoint. The stakes get raised with new information. This typically is also your “but if you don’t” moment, and will give the hero a course of action to follow.

Part 3, Attack: Midpoint information/awareness causes the protagonist to change course in how to approach the obstacles; the hero is now empowered with information on how to proceed, not merely reacting anymore; protagonist also ramps up battle with inner demons.

All is Lost/Black Moment. Part 3 ends with the protagonist losing all hope, finding the enemy too strong, or otherwise giving up (or considering it). This is closely followed by or the same as the Second Plot Point, where we learn the rest of the big picture, even if the hero doesn’t understand it yet.

Part 4, Resolution: The protagonist summons the courage and growth to come up with solution, overcome inner obstacles, and conquer the antagonistic force; all new information must have been referenced, foreshadowed, or already in play.

Finale. After the climax and final battle comes the resolution and the final image of where the hero’s success has brought him/the world. Paint pretty pictures that are directly in contrast with the introductory scenes.

That’s the basic structure I give to clients when they need some guidance on plotting a concept. It’s very similar to Derek Murphy’s 9-Step Plot Dot method touted by NaNo Prep 101. Whatever you choose to call them, I’ve used these to great success. I’d call those eight points your bare minimum outline. You may not have all of them yet, but those eight points should be your goal before November 1st. I have seen a slimmer five-milestone method based on K.M. Weiland’s Structuring Your Novel, but my personal feeling is that it’s too loose to be helpful when you get lost for whatever reason. I like the eight (or nine, if you follow Derek Murphy’s “return home changed” cycle).

Do you have all those already? Great, start breaking them down into scenes or chapters. Depending on your story, you may need many scenes to establish the setting, main characters, and get to the inciting incident. (Fantasy, SciFi, Westerns, Thrillers especially.) Keep in mind that you don’t need to start writing at the point that your characters get involved with the story. If it helps you, start with the lead-in scenes. Even if you cut them out later, they’ll get you started, and words written always count toward your NaNoWriMo word count total! I often find in fantasy or science fiction that I need more of a start to establish things, and ultimately I edit those scenes down to a few sentences that are key. I wouldn’t have been able to get there without writing out the scenes first to get them solidly in my own head.

Whew!

Yes, that was a longer entry than usual. I think it’s important to get started strong, and we’re now less than six weeks from November! I don’t know where the time has gone, I really don’t. It feels like yesterday I was scrambling to get that first overview post written up. I guess that was three weeks ago. I hope you’ve found these articles useful as you work on your concept for National Novel Writing Month!

Author’s Note: This is a big task, and while I’ve written it all as one objective here, this is really your goal for the next five weeks. For now, your task is the premise statement and then brainstorming on everything else I’ve mentioned, and you can worry about turning the ideas into more polished characters and plot points later. Next week I plan to do a run-down on different plotting methods, and then characters and setting aren’t going to be far behind. We’ll be working on each section of this concept one at a time, and there should be plenty of time to get into any areas you’re not confident with before November rolls around.